Take a look inside Turks Islands Landfall.

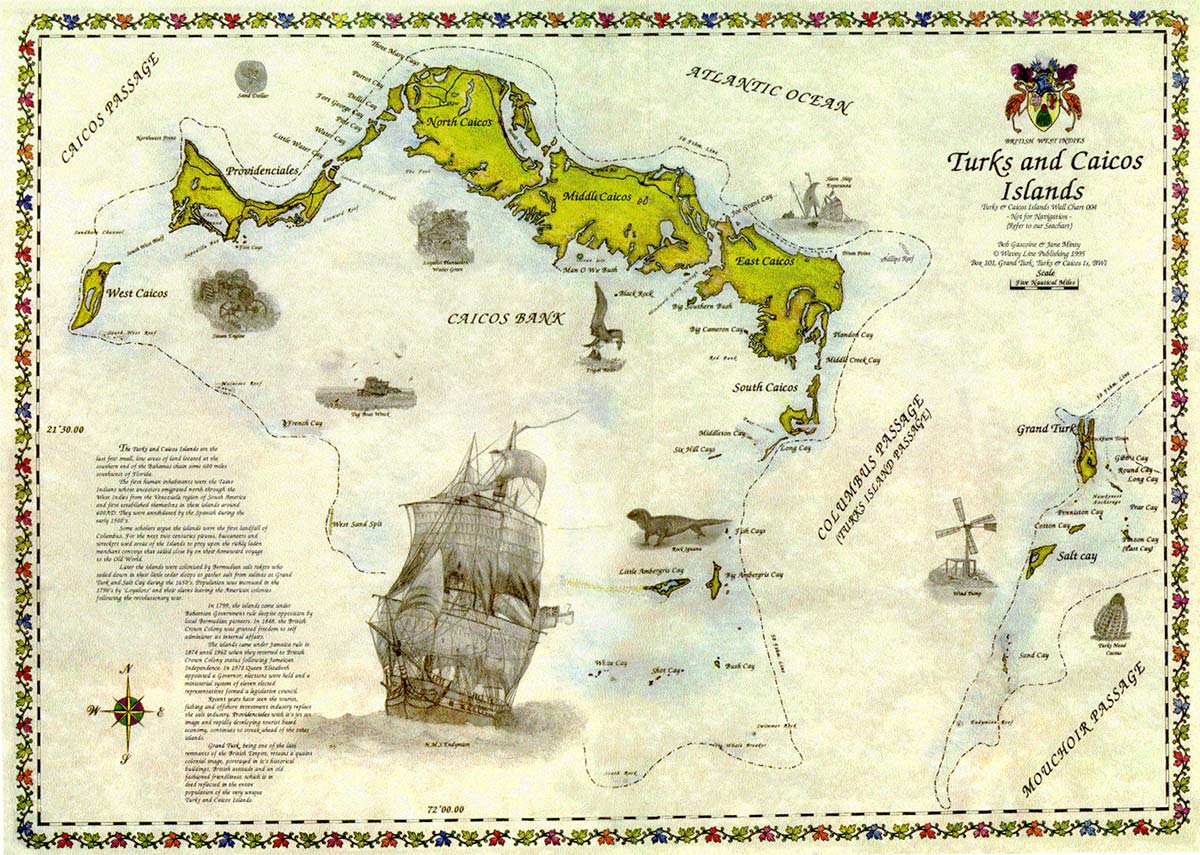

The work is divided into five main sections, each with several chapters charting the chronological developments in the Islands’ history and their progression into the current century. The narrative is embellished with historical photographs, illustrations, maps, charts and colour images.

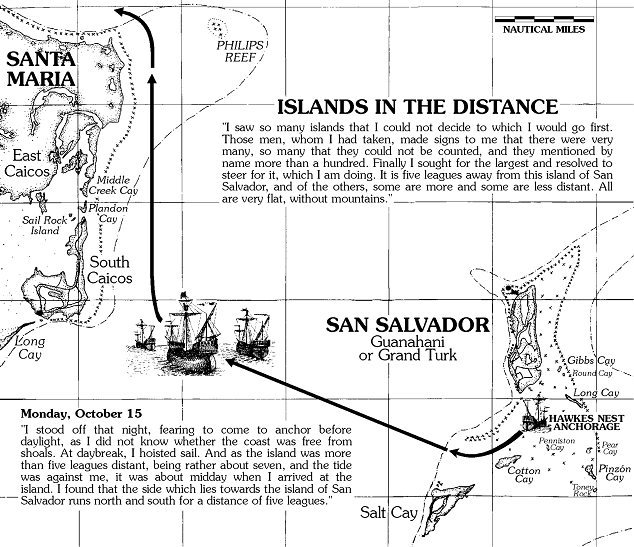

Part 1 presents a compelling and authoritative argument for the theory that Columbus made his first landfall on the island of Grand Turk, and gives an overview of the Lucayan culture existing on the islands at that time.

Part 2 covers the Islands’ history as a rendezvous for Caribbean pirates and the Bermuda privateers and mariners who pioneered the salt-making industry in the seventeenth century.

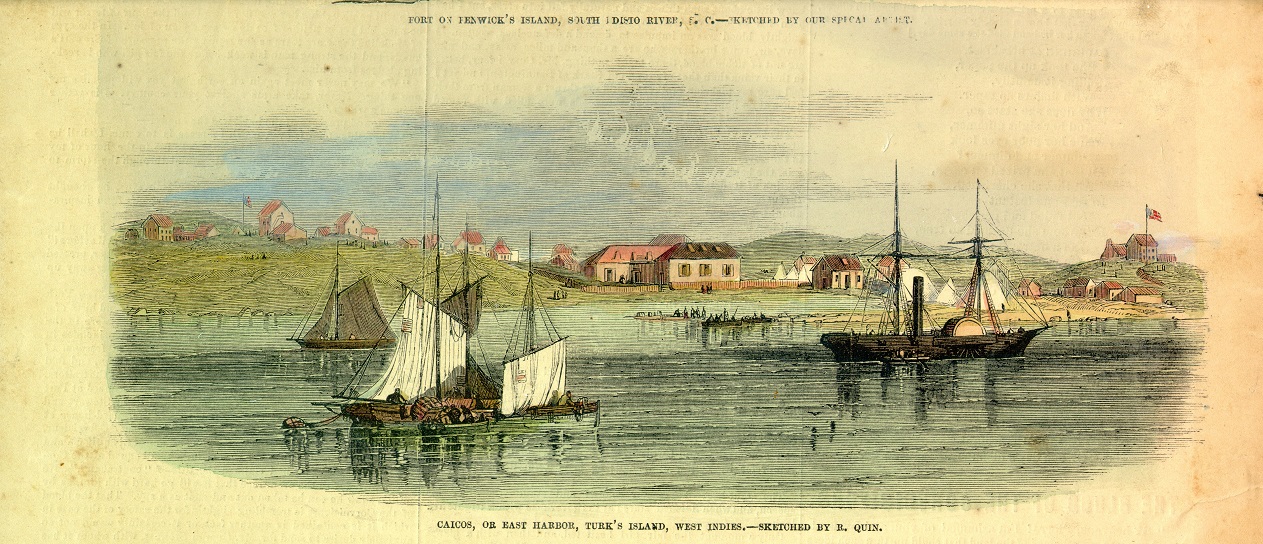

The settlement of the Turks and Caicos coincided with the European struggle for supremacy in the West Indies and the tiny, but strategically placed islands were variously claimed by Spain, France and finally held by England.

The above map shows the island of Grand Turk (Guanahani to the native Lucayans) as Colunbus’ San Salvador where he made his first landfall in the New World. Sadler quotes from the Journal in this depiction of the route Columbus followed from Guanahani or San Salvador to Island 2, called Santa Maria (or the Caicos Islands). Other charts in the book show the onward journey through the Caicos Islands to Cuba. Modified from Turks & Caicos Islands – Passage TC-001, Edition 1; Bob Gascoine and Jane Minty, Wavey Line Publishing, 1994.

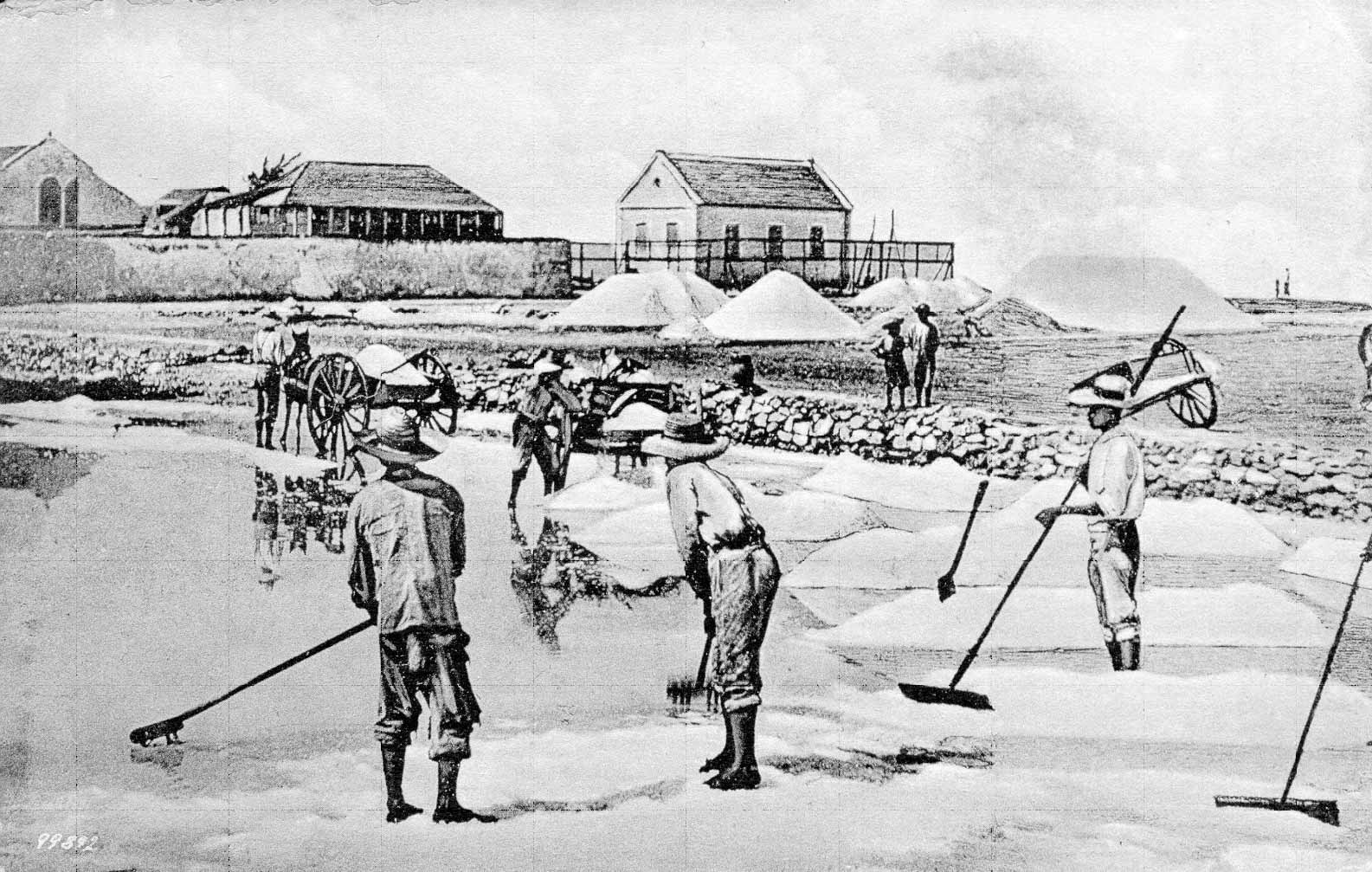

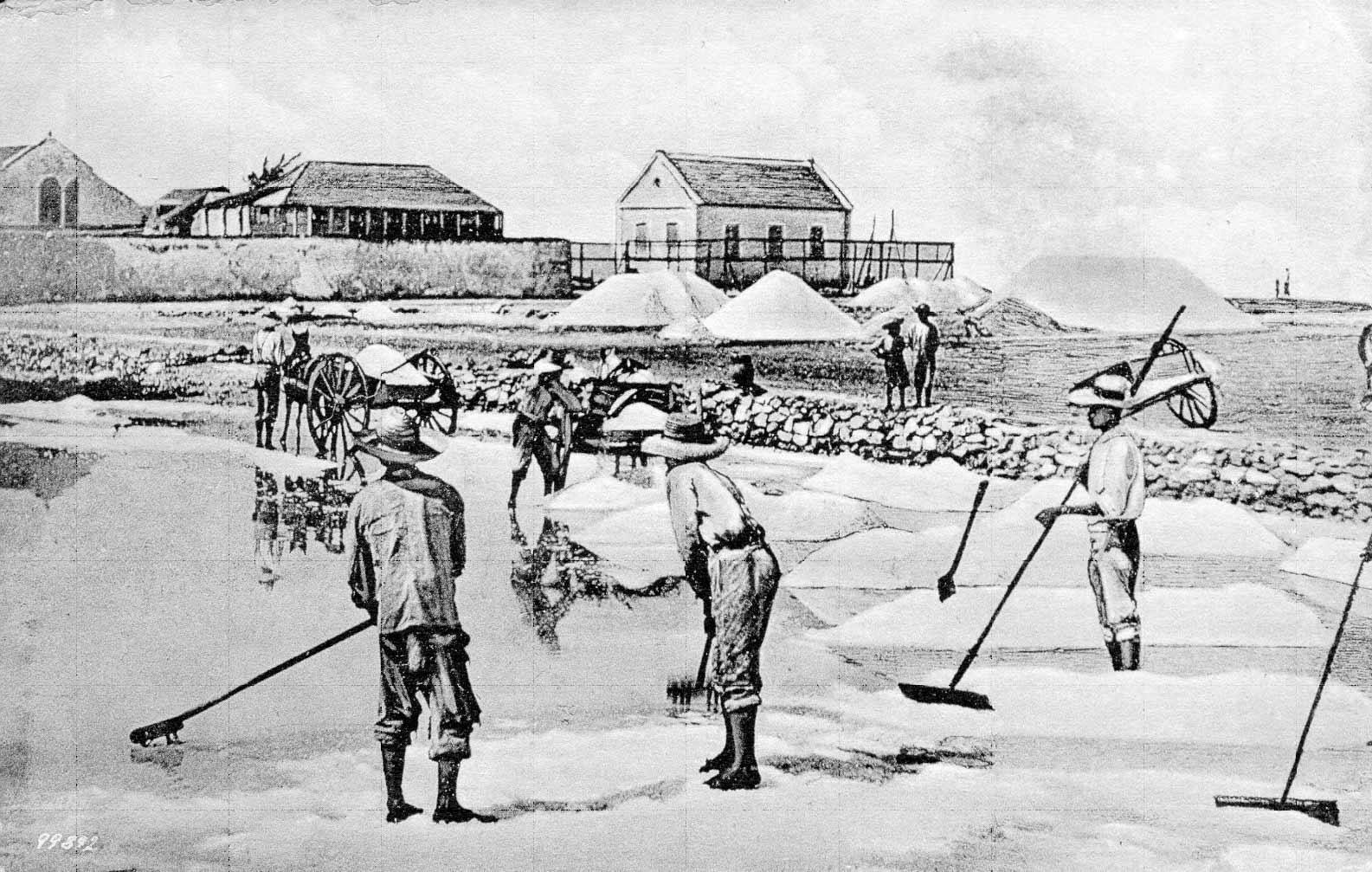

Raking Salt, Grand Turk, 1910 (Turks & Caicos National Museum)

The Islands’ salt trade with the American colonies played a pivotal role in the U.S. War of Independence as a clandestine trafficking of the valuable commodity to America contrived to evade the Navigational laws of Great Britain.

In the Eighteenth Century, the salt rakers were placed under a Bahamian custodianship which sought to regulate salt production and govern the restive Bermudian salt proprietors. Unhappy with the Bahamian administration, the Islands later successfully lobbied England for a form of self-government and separation from the larger colony.

During the period known as the Presidency, the islanders governed themselves for twenty-five years until bankruptcy forced them to become wards of Jamaica. The monoculture of salt created a precarious economy, but parts of the Caicos Islands followed the patterns of farming introduced by the exiled American Loyalist settlers and their slaves.

1860 sketch of East Harbour, South Caicos by R. Quin (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1862) Courtesy Turks and Caicos National Museum

Sadler traces the experiments in alternative crops – cotton, sisal, sponging, guano, farming – all of them marginal and short-lived; inevitably, “it was an almost impossible task to induce men accustomed to the irregular life of wrecking and salt raking … to submit to the monotonous routine necessary for remunerative results in agriculture.”

Following in the tradition of their Bermudian ancestors, the settlers took more readily to a life of seafaring and ‘wracking.’ Situated close to the French Colony on Hispaniola, the Islands were often catapulted into the maritime conflicts between the warring powers during the Napoleonic Wars and the Haitian Revolution. The nearby new black Republic of Haiti served as a magnet for hundreds of runaway slaves from Turks and Caicos who sought sanctuary on Haiti’s free soil. Today there is an ironic reverse migration as streams of Haitians seek economic refuge on TCI’s shores.

Loading Pita Fibre at Government Wharf, Grand Turk (Turks & Caicos National Museum)

“From the unprotected state of these islands, we have great reason to apprehend that our slaves may from the great facility of their escape, in small open vessels and from their naturally restless dispositions, be induced to abscond to Hayti.”

From Actg. King’s Agent at Turks Islands to Admiral of the British Fleet stationed at Port Royal, January 1821

Many of the countless shipwrecks in these waters are recounted here, including the renowned Spanish treasure galleon discovered by Sir William Phips on the ‘Silver Banks’ in 1687 and the ‘Molasses Reef Wreck’ which has the distinction of being the oldest shipwreck found in the Americas, whose relics are today preserved in the Islands’ Museum.

Many of the countless shipwrecks in these waters are recounted here, including the renowned Spanish treasure galleon discovered by Sir William Phips on the ‘Silver Banks’ in 1687 and the ‘Molasses Reef Wreck’ which has the distinction of being the oldest shipwreck found in the Americas, whose relics are today preserved in the Islands’ Museum.

The book examines the abandonment of the Colony’s outmoded salt economy in the post-war years, the exodus of much of the labour force seeking employment elsewhere, and the struggle to establish a niche for survival in the Twentieth Century.

The archipelago has now traded the hardships of salt-making for that of the other ‘white gold’ – its renowned beaches and white sands – which today make it a coveted resort of Caribbean tourism.